In “The deadly truth about a world built for men – from stab vests to car crashes”: (The Guardian) Caroline Criado-Perez explores which questions get asked in our research, and how they get asked.

In “The deadly truth about a world built for men – from stab vests to car crashes”: (The Guardian) Caroline Criado-Perez explores which questions get asked in our research, and how they get asked.

“The gender data gap is both a cause and a consequence of the type of unthinking that conceives of humanity as almost exclusively male.”

Just one example among many (cancer research, stab vests, safety masks, office temperature, bathroom access, nuclear testing, voice recognition technology, questions Siri can and cannot answer, and more):

Men are more likely than women to be involved in a car crash, which means they dominate the numbers of those seriously injured in them. But when a woman is involved in a car crash, she is 47% more likely to be seriously injured, and 71% more likely to be moderately injured, even when researchers control for factors such as height, weight, seatbelt usage, and crash intensity. She is also 17% more likely to die. And it’s all to do with how the car is designed – and for whom.

Women tend to sit further forward when driving. This is because we are on average shorter. Our legs need to be closer to reach the pedals, and we need to sit more upright to see clearly over the dashboard. This is not, however, the “standard seating position”, researchers have noted. Women are “out of position” drivers. And our wilful deviation from the norm means that we are at greater risk of internal injury on frontal collisions. The angle of our knees and hips as our shorter legs reach for the pedals also makes our legs more vulnerable. Essentially, we’re doing it all wrong.

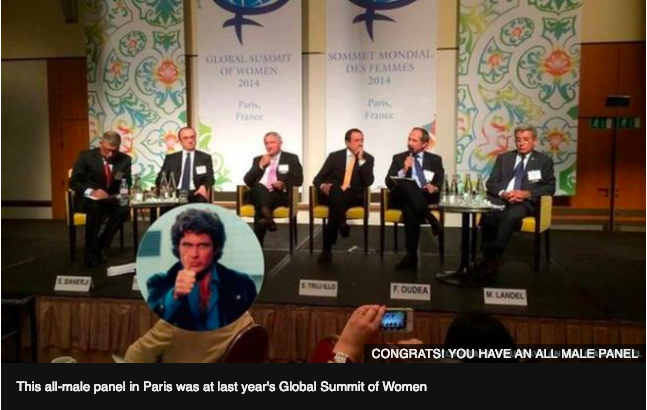

Congratulations–and gratitude–to faculty members

Congratulations–and gratitude–to faculty members  The journal Nature offers advice to and from male scientists in

The journal Nature offers advice to and from male scientists in

In her op-ed in USA Today titled

In her op-ed in USA Today titled  Last week, JHU chemistry professor

Last week, JHU chemistry professor